Research summary: Perthes’ disease and hip impingement

Changes to the shape of the hip joint caused by Perthes’ disease are linked to problems such as hip pain and arthritis later in life. But how exactly does deformity result in bad outcomes? One part of my PhD thesis looked into this question, and is available open access in the Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics as:

For a brief and hopefully more accessible summary, read on…

The problem after Perthes’

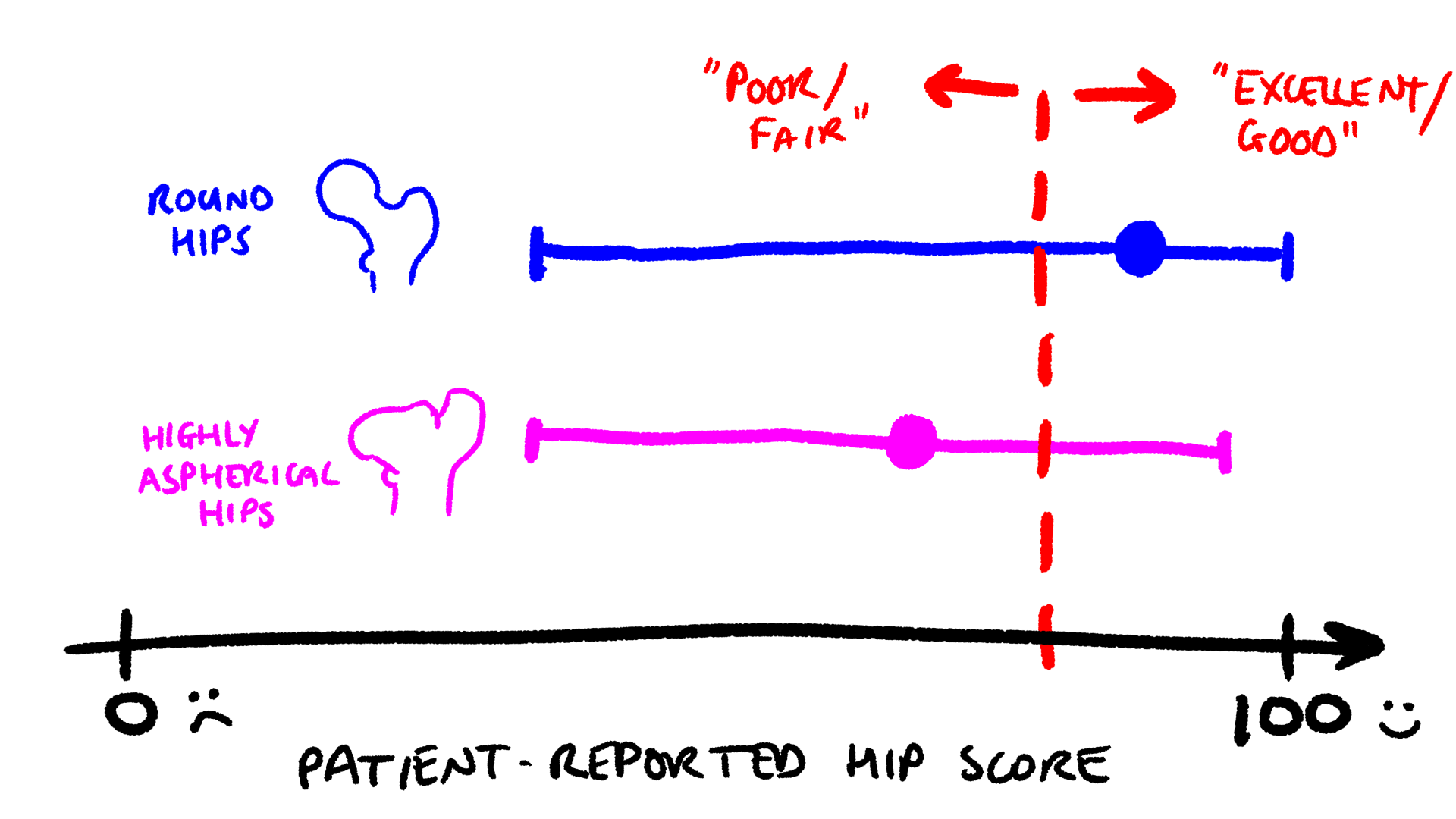

As I outlined in my previous research summary, Perthes’ disease often results in longer-term problems for patients like chronic hip pain and early-onset osteoarthritis after their recovery during childhood. We know that the final shape of the joint plays a big role in causing these outcomes. For example, we know that aspherical hips have worse outcomes on average than hips that appear round on X-rays. However, due to the highly variable nature of residual Perthes’ deformity, it is not as useful to predict outcomes for individual patients:

Studies that follow up with people who had Perthes’ disease have shown that patients with highly aspherical hips report lower average outcome scores (round markers) than patients with round hips. However, the range of outcomes (horizontal bars) for each group is almost the same. Sketch based on data from Larson et al. (2012).

This is a big problem. Patients reasonably want to know how likely they are to have hip pain or arthritis, and when. How long can they expect good quality of life and mobility? Forty years? Twenty? Five? These are not questions that can be answered at the moment, for two main reasons:

- Complex and three-dimensional joint shape can’t be represented well on 2D X-rays, and

- Measurements of shape only indirectly describe function—how the hip moves around during daily life.

One important way that a change in shape can influence hip function is through impingement. This is where bones in the hip joint bump into each other, damaging the more fragile cartilage and other tissues that get caught between them. The video below shows an animation of cam-type impingement, caused by a bony protrusion on the femur side of the hip joint.

Hip impingement is quite a common phenomenon, particularly in athletes like Andy Murray1, and is connected to pain and the development of osteoarthritis. Because of this, impingement is also thought to be one of the main factors that cause poor long-term outcomes people with Perthes’ disease deformity.

The relationship between X-ray measurements of hip joint shape and impingement are unclear in Perthes’, so in this study we adapted existing methods for measuring impingement to a Perthes’ disease context to determine whether shape changes seen on X-rays can predict an increased potential for impingement.

What we did

To answer this question, we recruited 17 participants who had been treated for Perthes’ at BC Children’s Hospital. We then took some unusual magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of all of their hips that had Perthes’ deformity (people often only get Perthes’ in one hip—we didn’t include the other, unaffected, hips in this study).

Upright open MRI

When you think of a MRI scanner, you might normally imagine a machine that looks like this:

And you’d be right. Your typical MRI scan involves getting shoved into a tube surrounded by an elongated doughnut that’s stuffed full of magnets.

Here at the Centre for Aging SMART we have a different kind of MRI called an upright open MRI scanner. Open MRI designs have benefits and downsides compared to standard MRI machines; the key advantage for our research is there is enough room for our participants to move their hips into different positions. This means we can take pictures of hip impingement as it happens.

Imaging and measurement

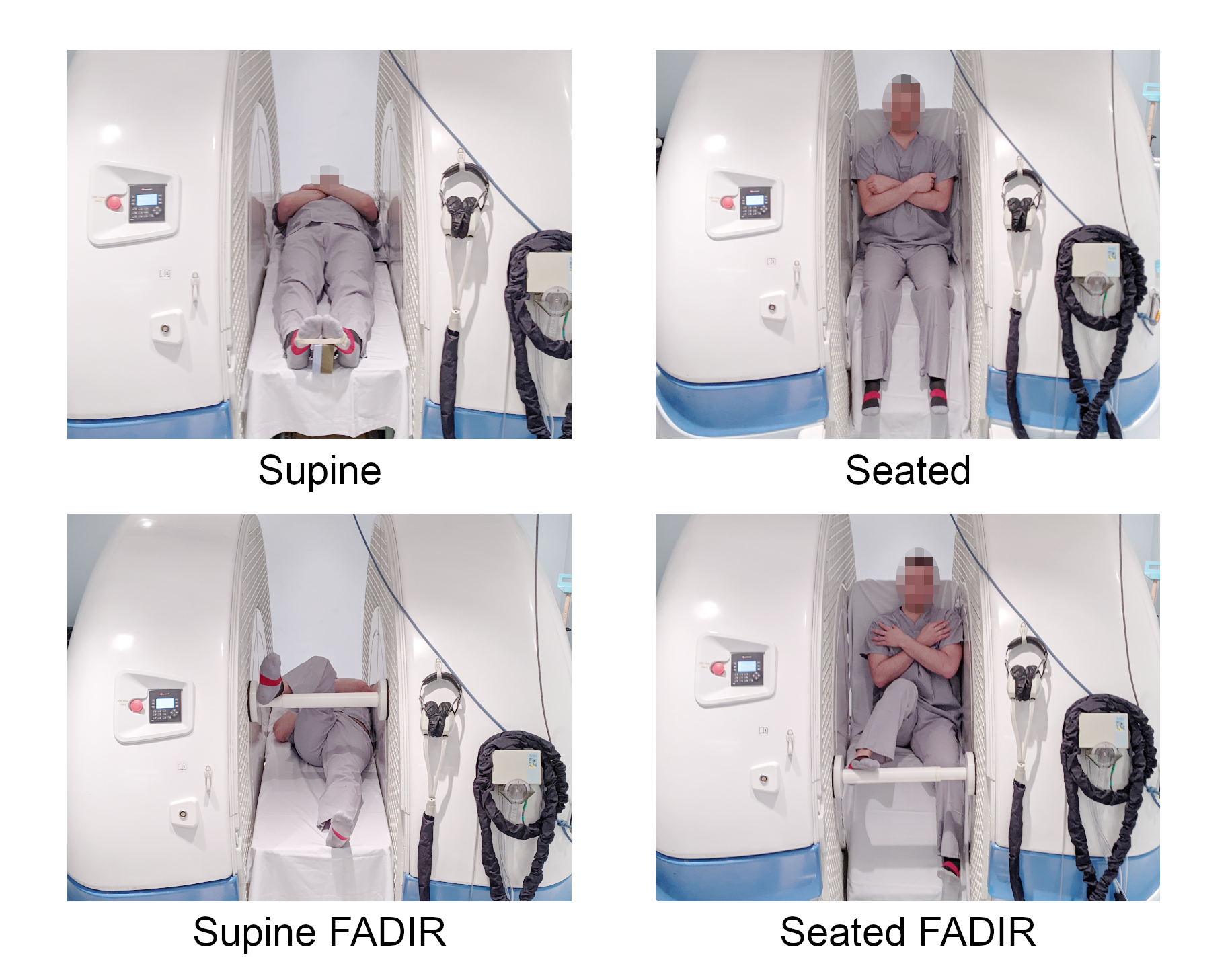

In our study, we scanned hips in four postures. These postures were chosen to represent a range of joint positions with increasing flexion, with the high flexion, adduction, and internal rotation (FADIR) postures considered to be particularly “at-risk” positions for impingement. The scanning session could take up to three hours for each hip, so we were very lucky to have exceptionally patient patients (heh heh).

The four postures used for hip imaging in this study. In order of increasing flexion: supine with a neutral hip position; seated neutral; supine with the hip flexed; adducted and internally rotated (FADIR); and seated FADIR.

From each hip scan we could measure the potential for impingement using the idea of “clearance”, which effectively means how far the hip can rotate before bony structures bump into each other. This angle of rotation is denoted by β.

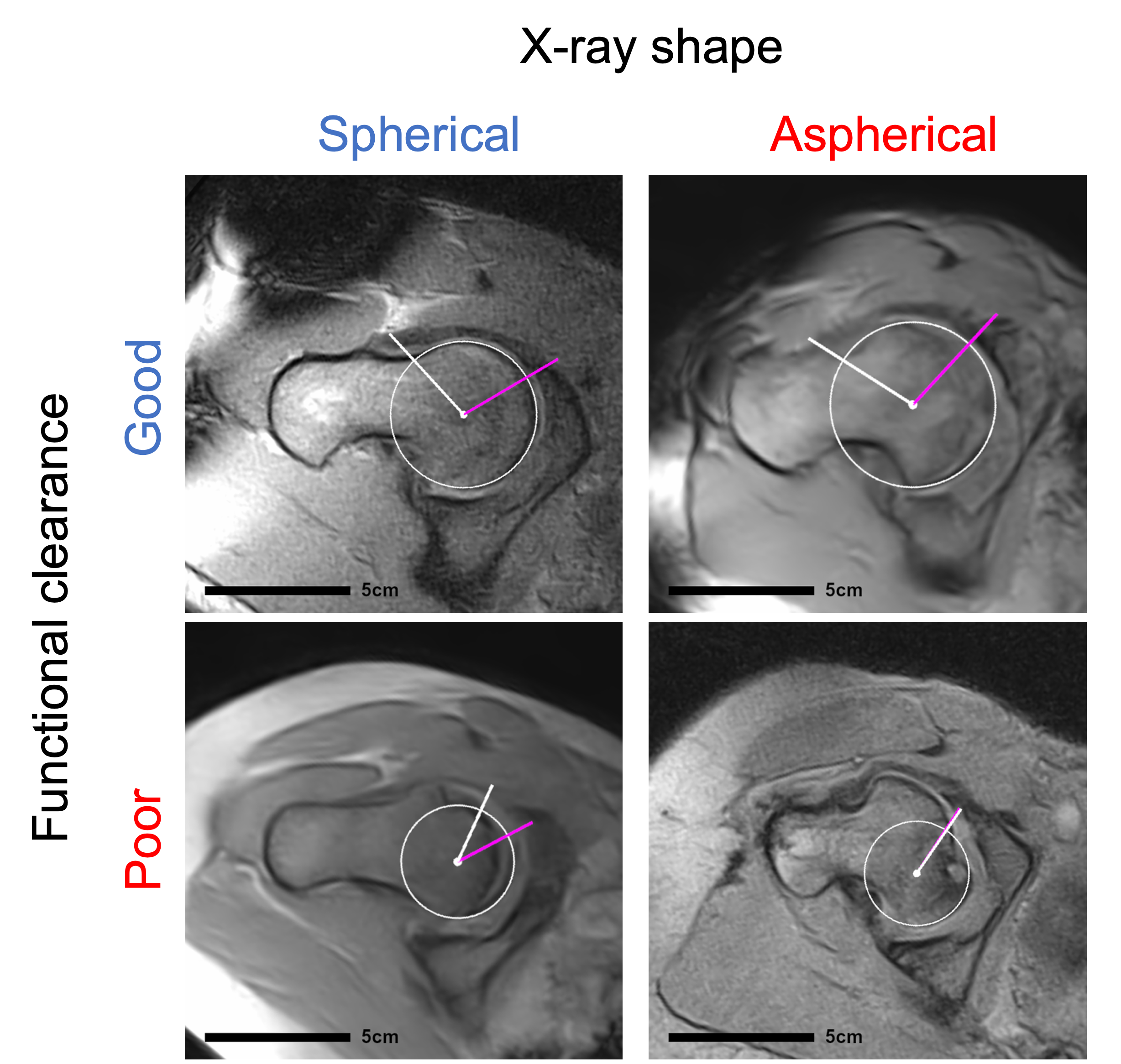

Hips with large β (high clearance, top row) can rotate smoothly without difficulty. Hips with low clearance (bottom row) cannot rotate far before bony impingement.

What we found

We split the hips in this study into two groups based on their X-ray shape: a spherical group with “mild” deformity and an aspherical group with “severe” deformity. On average, the aspherical hips had significantly less clearance (difference in β = -39.1°) than hips in the spherical group across all of the imaged postures, suggesting a substantially greater potential for impingement during daily activities in aspherical hips.

However, there is a broad range of β in each group and a large overlap between the spherical and aspherical groups, caused primarily by a small number of hips that appear spherical on X-rays but have poor clearance, and vice versa.

Most hips that look round on X-rays had good clearance in the MRI (top left), but some had poor clearance (bottom left). Similarly, most aspherical hips had poor clearance (bottom right), but some looked well rounded in the MRI view (top right).

The overall conclusions, therefore, are:

- X-ray measurements of hip joint shape are associated on average with functional outcomes like reduced clearance and an increased potential for impingement, but

- There is often a disconnect between shape and function in individual patients with Perthes’ deformity.

In future, it would be useful to study whether our X-ray measurements of shape could be modified to take clearance into account. If such modifications can improve patient-specific prediction of long-term outcomes after Perthes’ disease, it could go a long way towards helping patients manage their condition with their doctors, and maintain mobility and a high quality of life for longer.

-

Contrary to the article’s title, Murray did not retire after his hip resurfacing surgery. He even won the European Open the same year, and only retired last year after the Paris Olympics. ↩︎

Comments

You can use your Mastodon or other Fediverse account to comment on this post by replying to this thread.

Alternatively, you can reply to this Bluesky thread using a bridged Bluesky account.

Learn how this is implemented here.