Research summary: cartilage health after Perthes’ disease

Update 26th January 2026: this paper was selected by Arthritis Society Canada as one of their Top 10 Research Advances of 2025! I’m incredibly honoured to be recognised by Arthritis Society Canada, and I would not have been able to complete my PhD research without their support.

That’s right, you get two summaries for the price of one this month. By a quirk of the peer review process and copyediting timeline, two of my PhD thesis chapters were published as journal articles within a week of each other! See here for my summary of the other one.

The article summarised here investigates the role of Perthes’ disease—a condition which can cause a permanent change to the shape of the hip joint (deformity) during childhood—in how cartilage health changes during adolescence and young adulthood. The full text is available open access in Osteoarthritis and Cartilage Open as:

A little motivation

During my PhD work, I have had the opportunity to meet some wonderful and engaged people who had had Perthes’ disease when they were younger. In between MRI scans, there was often downtime where we could talk about their experiences and outlook. Some themes came up over and over again: uncertainty about their longer-term mobility, frustration at the lack of patient resources after leaving the Children’s Hospital system, and concerns about not being taken seriously if they were “too young” to have hip problems or pain.

Unfortunately, the root cause of these uncertainties is simply that the long term impacts of Perthes’ disease are still very poorly understood—by us as doctors and researchers, not just by patients. Despite knowing that adults with Perthes’ deformity develop hip arthritis at a very high rate (see below), and that they have much worse pain and quality of life than typical adults, there are currently no clinical guidelines for preventative, non-surgical treatments that could reduce or delay the onset of pain. Treatment of Perthes’ deformity is reactive in response to pain, rather than proactive.

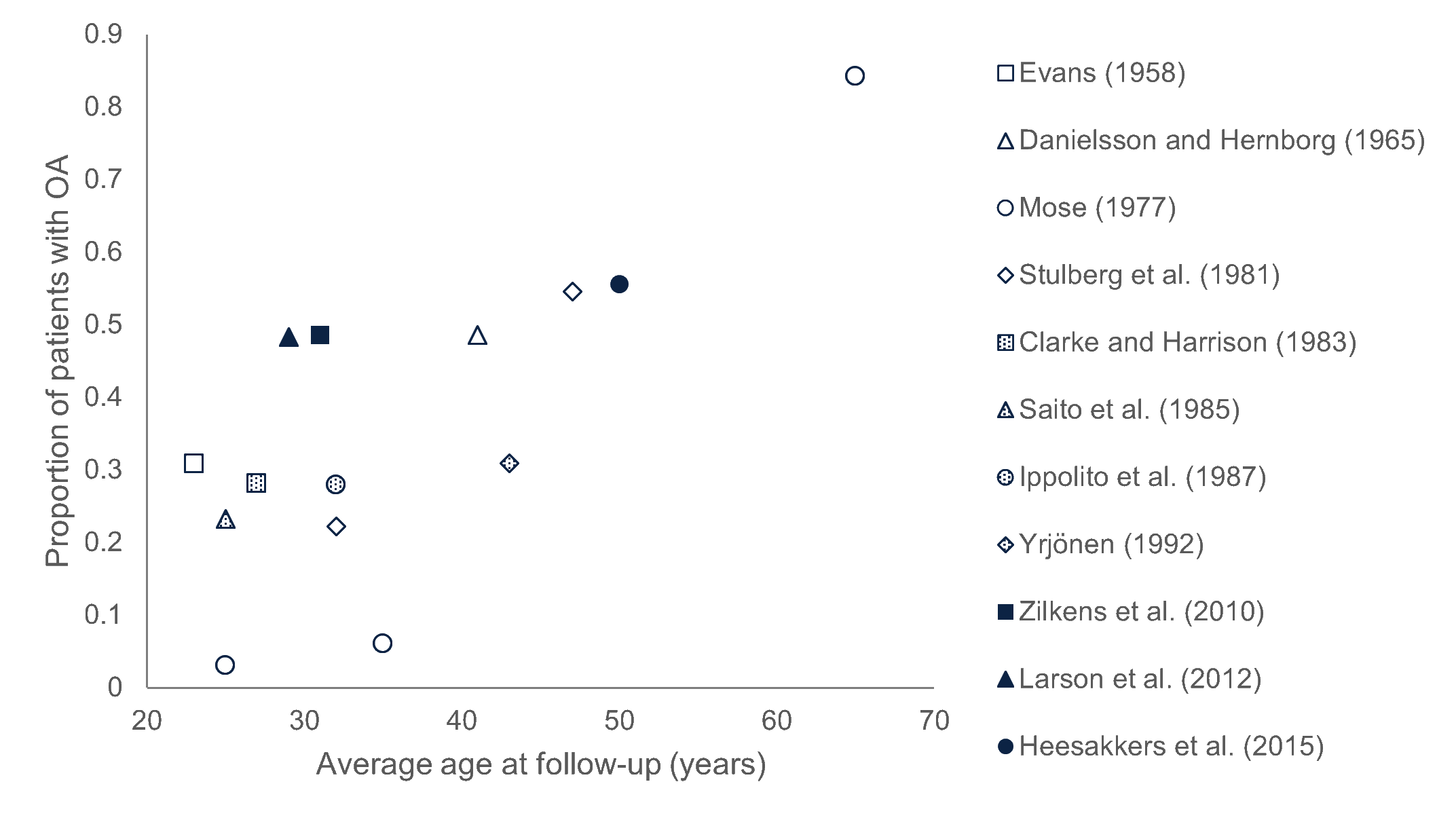

Long-term follow-up studies of people with residual Perthes’ deformity have shown very high rates of hip osteoarthritis (OA) that increase with age. On the vertical axis, a proportion of 1.0 represents 100% of patients, so a proportion of 0.5 would mean 50% of the patients in that study had arthritis. For context, only 2% of typical 50-54 year olds have hip arthritis.

One of the barriers to more effective treatment of Perthes’ deformity is that we don’t know when damage to the joint’s cartilage (the smooth, rubbery material that covers the end of our bones) begins after “healing” from the condition, and how quickly the damage worsens. Our main objective in this study was to use advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure cartilage damage and see how it changes with age in hips with Perthes’ deformity compared to hips without.

What we did

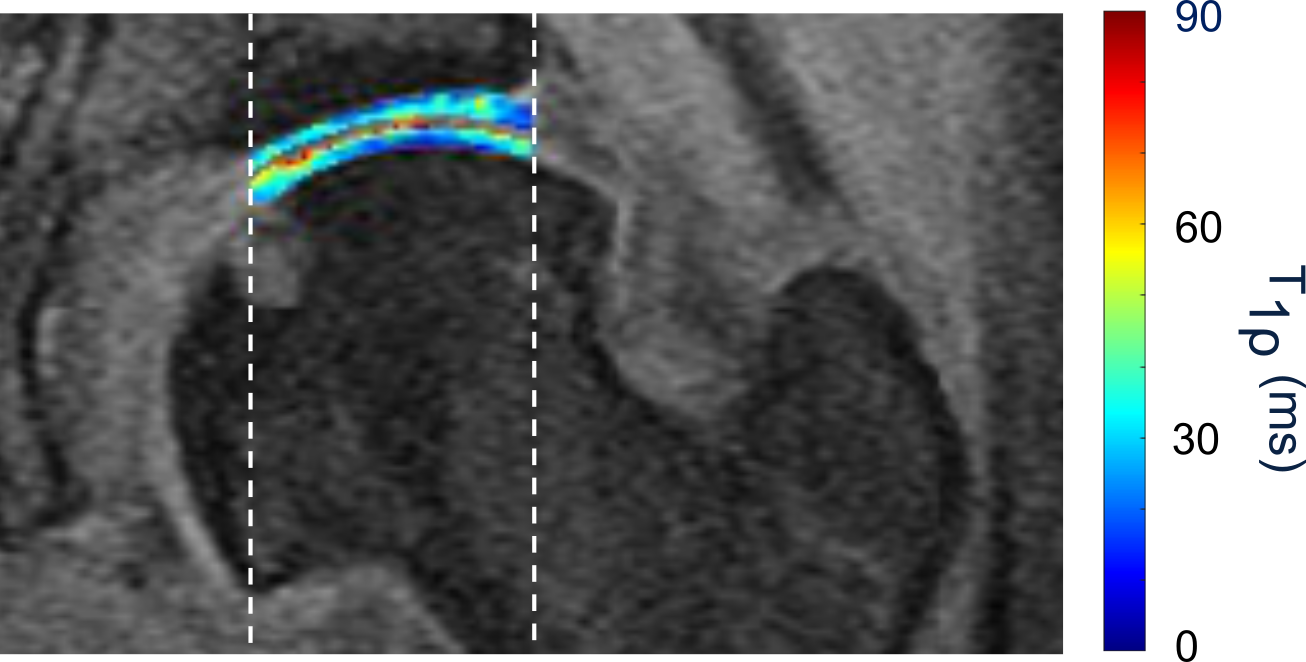

The participants for this study were the same 17 people (aged 11-24 years) who took part in the upright open MRI study. We also added in 15 control participants, who had never had any hip problems. We scanned the participants’ hips using a technique called T1ρ imaging1 at the 3T Research MRI at BC Children’s Hospital, and calculated the average T1ρ relaxation time in their hip joint’s cartilage. In adults, an increase in T1ρ indicates pre-arthritic changes in the structure and chemistry of joint cartilage long before they become visible on ordinary MRI or X-rays.

This figure shows an example of a T1ρ colourmap in hip cartilage, overlaid on the greyscale MRI slice of the same hip. Vertical dashed lines indicate the part of the cartilage that normally bears the body’s weight.

What we found

Our main finding was that cartilage health changes differently with age in hips with Perthes’ deformity compared to those without. In hips without Perthes’ deformity, the T1ρ relaxation time actually decreased in older participants, but this doesn’t mean their cartilage was getting healthier with age! The decrease actually reflects normal changes that happen to cartilage during adolescence, and is backed up by evidence from other research—but this is the first time these normal changes have been measured using T1ρ. This gives us an important baseline to compare against when we look at hips with Perthes’ deformity.

T1ρ decreased through adolescence and young adulthood in hips without Perthes’ deformity (blue), diverging from hips with Perthes’ deformity (red).

In the youngest participants, the hips with Perthes’ deformity had similar T1ρ to those without, but the two groups diverged through adolescence. By age 25, a typical hip with Perthes’ deformity is expected to have T1ρ more than 15% higher than a healthy adult hip, indicating substantial cartilage degradation already by young adulthood.

Our results suggest that cartilage damage after Perthes’ disease is mostly a progressive process that begins soon after after the hip is considered “healed” and is likely related to the altered mechanics of the hip joint due to the residual deformity. This does not entirely rule out other factors that might influence cartilage health such as inflammation, and the study is limited in that we didn’t follow the same participants over time to track progressive degradation in each hip.

However, this research helps us better understand when and how cartilage damage occurs in people with Perthes’ deformity. This knowledge could be important for developing ways to prevent or delay the onset of hip arthritis in these individuals and improve their long-term quality of life.

-

That funny “p” is the Greek letter rho (ρ). This means we pronounce T1ρ as “tee-one-row”! ↩︎

Comments

You can use your Mastodon or other Fediverse account to comment on this post by replying to this thread.

Alternatively, you can reply to this Bluesky thread using a bridged Bluesky account.

Learn how this is implemented here.